Brutalist London

Having decided it was time again to see some brutalism, I set out for London. My route took me to five brutalist housing developments, the Barbican Centre in the City, Balfron Tower in Tower Hamlets, Southwyck House in Brixton, Trellick Tower in Kensal Town and Alexandra Road Estate in Camden.

Barbican Centre is by far the largest and best known of these. Located in an area once devastated by World War II bombings, it was intended as and remains an upmarket residential estate. The individual towers were completed from 1969 to 1976. A distinguishing feature is the use of highwalks, one to three levels above ground, to achieve a separation of cars, parking or driving in the levels below. As a result the estate is a car free island in one of the busiest parts of London.

Next up was Balfron Tower in Poplar near Canary Wharf. Commissioned by the London County Council, it prompted fierce criticism when it opened in 1968. “Although perversely beautiful,” wrote Guardian journalist Terence Bendixson, the tower “conjures up thoughts of prisons and pillboxes.” Architect James Dunnett attributed it a “delicate sense of terror”.

Strapped for cash, the council sold the building to a private developer in 2007. After a painfully long redevelopment phase, the new flats received phenomenal interest from wealthy buyers, but in the end not a single one was sold which forced the developer to convert them into “professionally managed rented homes”. The apartments are tastefully furnished in a postmodern, retro-futuristic style like the one in figure 1. At the time of writing a few were available for renting.

Southwyck House in Brixton is of particular interest to me since it features in my third novel ‘The True Story’. With a harsh, blocky façade and small windows, it looks even more like a prison than Balfron Tower. In fact, this was intended by the architect Magda Borowiecka whose brief was to design the building as a noise barrier, shielding the inhabitants from an inner orbital motorway up to 60 feet in the air. When it became clear that the flyover would never be built, it was too late to change the design.

Completed in 1981, it is the youngest of the five estates, but also the one with the most dramatic beginnings. The Brixton riots happened right after it had opened. From the start it was plagued with squatters, burglaries and drug abuse. By the mid-80s it had become a prime example of a crime ridden, run down, inner city council estate. Security measures in 1990 have made the block safer but even more so the general gentrification of Brixton.

Inside the block, it has always been a different story. With large windows and balconies at the rear, the apartments provide bright and spacious accommodation.

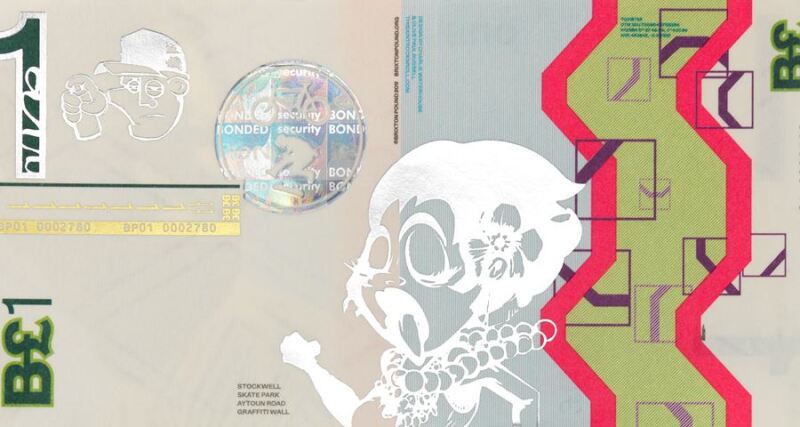

Southwyck house, embodied by its zigzag line, has become a style icon in Brixton that can be found in logos of local businesses or on the Brixton Pound.

Trellick Tower in Kensal Town and its younger sibling Balfron Tower were both designed by architect Erno Goldfinger. If the name sounds familiar it is likely because Ian Fleming chose the same name for his most iconic villain. While Fleming was acquainted with the architect, the various rumours explaining the choice of name by a disagreement between the two men may not be true. Instead Fleming may have picked the name simply because he liked it.

During the late 1970s, Trellick Tower had been a scene of crime and anti-social behaviour. At one point, the building was without electricity or a functioning lift for a longer period causing human tragedies which earned it the nickname "The Tower of Terror". This changed with the introduction of the "right to buy" in 1980, allowing tenants to buy their homes at a discounted price. Having done that, residents took matters in their own hands and introduced many security features that proved effective. In recent years, Trellick Tower has become a London icon, appearing on T-shirts, adverts, films and songs.

My last destination was the Alexandra Road Estate in Camden. Like Southwyck House it is constructed as a noise barrier, but this time against a major railway line that runs alongside its eight-story ziggurat like construction.

It represents a departure from the earlier choice using tower blocks surrounded by open space going back to a form of terraced housing. Thankfully it didn’t experience the problems and vandalism of other council estates in London and is now regarded as one of the most important examples of social housing in Europe.